Mrs Ann White and Baby Daughter Abducted by Apache?

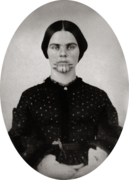

| Olive Oatman | |

|---|---|

Olive Oatman c. 1863 [1] | |

| Born | Olive Ann Oatman September 7, 1837 La Harpe, Illinois |

| Died | (aged 65) Sherman, Texas, U.S. |

| Resting identify | West Colina Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Olive Oatman Fairchild, Oach |

| Alma mater | Academy of the Pacific |

| Spouse(south) | John Brant Fairchild (m. 1865) |

| Children | 1 |

Olive Ann Oatman (September 7, 1837 – March 21, 1903)[2] was a woman born in Illinois. In 1851, while traveling from Illinois to California with a visitor of Brewsterites, the family unit was attacked past a small group from a Native American tribe. Though she identified them as Apache, they were most likely Tolkepayas (Western Yavapai). They clubbed many to death, left her brother Lorenzo for dead, and enslaved Olive and her younger sis Mary Ann, holding them captive for i year earlier they traded them to the Mohave people.[3] [4] : 85 While Lorenzo exhaustively attempted to recruit governmental help in searching for them, Mary Ann died from starvation and Olive spent four years with the Mohave.

V years after the attack, she was repatriated into American lodge. The story of the Oatman Massacre began to exist retold with dramatic license in the press, as well as in her own memoir and speeches. Novels, plays, movies, and poetry were inspired, which resonated in the media of the time and long afterward. She had become an oddity in 1860s America, partly because of the prominent bluish tattooing of her face past the Mohave, making her the offset known white woman with Native tattoo on record.[v] Much of what really occurred during her fourth dimension with the Native Americans remains unknown.[6] : 146–51

Early life [edit]

Born into the family unit of Mary Ann (née Sperry) and Royce Oatman, Olive Oatman was one of vii siblings. She grew upwards in the Mormon religion.

In 1850, the Oatman family joined a wagon train led by James C. Brewster, a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-twenty-four hour period Saints, whose attacks on and disagreements with the church leadership in Common salt Lake City, Utah had caused him to break with the followers of Brigham Young in Utah and pb his followers – Brewsterites – to California, which he claimed was the "intended place of gathering" for the Mormons.[seven] [8]

The Brewsterite emigrants, numbering between 85 and 93, departed Independence, Missouri, on August 5, 1850. Dissension caused the group to separate well-nigh Santa Fe in New Mexico Territory with Brewster following the northern route. Royce Oatman and several other families chose the southern route via Socorro and Tucson. Almost Socorro, Royce Oatman causeless command of the party. They reached New Mexico Territory early on in 1851 only to find the land and climate wholly unsuited to their purpose. The other wagons gradually abandoned the goal of reaching the oral cavity of the Colorado River.[7]

The party had reached Maricopa Wells, when they were told that not but was the stretch of trail ahead barren and dangerous, but that the Native Americans ahead were very hostile and that they would run a risk their lives if they proceeded further. The other families resolved to stay. The Oatman family, somewhen traveling alone, was nearly annihilated in what became known as the "Oatman Massacre" on the banks of the Gila River about eighty–90 miles (130–140 km) eastward of Yuma, in what is now Arizona.[9]

Oatman massacre [edit]

The Oatman Family Massacre site.

Mary Ann and Royce Oatman had vii children, and Mary Ann was pregnant with their eighth during their journeying from Illinois to the Gila River. The Oatman children ranged in age from one to 17, the eldest being Lucy Oatman. On the Oatmans' quaternary solar day out from Maricopa Wells, they were approached by a group of Native Americans who were request for tobacco and food.[8] Due to the lack of supplies, Royce Oatman was hesitant to share as well much with the pocket-sized party of Yavapais. They became irate at his stinginess. During the encounter, the Yavapais attacked the Oatman family unit. The Yavapais clubbed the family to decease. All were killed except for three of the children: 15-year-erstwhile Lorenzo, who was left for dead, and 14-year-old Olive and 7-year-sometime Mary Ann, who were taken to be slaves for the Yavapais.[9]

After the attack, Lorenzo awoke to find his parents and siblings expressionless, but he saw no sign of little Mary Ann or Olive. Lorenzo attempted the hazardous trek to find help. He eventually reached a settlement, where his wounds were treated. Lorenzo rejoined the emigrant railroad train, and three days later returned to the bodies of his slain family unit. In a detailed retelling which was reprinted in newspapers over the decades, he said, "We buried the bodies of male parent, mother and babe in ane mutual grave."[ten] The men had no way of excavation proper graves in the volcanic rocky soil, and so they gathered the bodies together and formed a cairn over them. Information technology has been said the remains were reburied several times and finally moved to the river for re-interment by early Arizona colonizer Charles Poston.[11] Lorenzo Oatman became adamant to never give up the search for his only surviving siblings.[10]

Abduction and captivity [edit]

Olive and Mary Ann Oatman[12]

After the set on, the Native Americans took some of the Oatman family's belongings, forth with Olive and Mary Ann. Although Olive Oatman subsequently identified her captors equally members of the Tonto Apache tribe,[13] [xiv] they were probably of the Tolkepaya tribe (Western Yavapais)[4] : 85 living in a village eight miles (13 km) southwest of Aguila, Arizona, in the Harquahala Mountains. After arriving at the village, the girls were initially treated in a way that appeared threatening, and Oatman after said she idea they would exist killed. However, the girls were used as slaves to fodder for food, to lug water and firewood, and for other menial tasks; they were often browbeaten.

During the girls' stay with the Yavapais, some other grouping of Native Americans came to trade with the tribe. This group was fabricated up of Mohave Native Americans. The daughter of the Mohave Chief Espaniole saw the girls and their poor treatment during a trading trek. She tried to make a merchandise for the girls. The Yavapais refused, but the chief's daughter, Topeka, was persistent and returned one time more than offering a trade for the girls. Somewhen the Yavapais gave in and traded the girls for two horses, some vegetables, blankets, and beads. After being taken into Mohave custody, the girls walked for days to a Mohave village along the Colorado River (in the centre of what today is Needles, California). They were immediately taken in by the family of a tribal leader (kohot) whose non-Mohave proper noun was Espianole. The Mohave tribe was more prosperous than the group that had held the girls captive, and both Espaniole's wife, Aespaneo, and daughter, Topeka, took an interest in the Oatman girls' welfare. Oatman expressed her deep affection for these 2 women numerous times over the years afterward her captivity.[4] : 93

Aespaneo arranged for the Oatman girls to be given plots of land to farm. A Mohave tribesman, Llewelyn Barrackman, said in an interview that Olive was most likely fully adopted into the tribe because she was given a Mohave nickname, something only presented to those who have fully assimilated into the tribe. Olive herself would afterward claim that she and Mary Ann were held convict past the Mohave and that she feared to leave, but this statement could have been colored by the Reverend Purple Byron Stratton, who sponsored the publication of Olive'southward captivity narrative shortly later her render to White club. For case Olive did not effort to contact a large grouping of whites that visited the Mohaves during her period with them,[four] : 102 and years later on she went to come across with a Mohave leader, Irataba, in New York Metropolis and spoke with him of old times.[4] : 176–77

Anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber wrote in an article almost the Oatman captivity: "The Mohaves always told her she could go to the white settlements when she pleased just they dared not go with her, fearing they might be punished for having kept a white woman then long among them, nor did they cartel to let it be known that she was among them".[15]

Some other matter that suggests Olive and Mary Ann were non held in forced captivity by the Mohave is that both girls were tattooed on their chins and arms,[16] [17] [xviii] in keeping with the tribal custom. Oatman later claimed (in Stratton's book and in her lectures) that she was tattooed to mark her every bit a slave, but this is not consistent with the Mohave tradition, where such marks were given only to their ain people to ensure that they would enter the land of the dead and exist recognized there past their ancestors equally members of the Mohave tribe.[6] : 78 The tribe did not intendance if their slaves could accomplish the land of the dead, withal, so they did not tattoo them. It has also been suggested that the evenness of Olive's facial markings may point her compliance with the procedure.[ commendation needed ]

Olive Oatman 1860s lecture notes tell of her younger sister often yearning to join that better "world" where their "Father and Female parent" had gone.[nineteen] Mary Ann died of starvation while the girls were living with the Mohave. This happened in nigh 1855–56, when Mary Ann was ten or eleven. Information technology has been claimed[ by whom? ] that there was a drought in the region,[four] : 105 and that the tribe experienced a dire shortage of food supplies, and Olive herself would have died had not Aespaneo, the matriarch of the tribe, saved her life by making a gruel to sustain her.[ citation needed ]

Olive later spoke with fondness of the Mohaves, who she said treated her improve than her commencement captors. She nigh likely considered herself alloyed.[20] She was given a clan proper name, Oach, and a nickname, Spantsa, a Mohave word having to practice with unquenchable animalism or thirst.[6] : 73–74 [21] And she chose not to reveal herself to white railroad surveyors who spent nearly a week in the Mohave Valley trading and socializing with the tribe in February 1854.[half dozen] : 88 Considering she did non know that Lorenzo had survived the massacre, she believed she had no immediate family, and the Mohave treated her as 1 of their own.[ commendation needed ]

Release [edit]

When Olive was nineteen years former, Francisco, a Yuma Indian messenger, arrived at the village with a message from the authorities at Fort Yuma. Rumors suggested that a white girl was living with the Mohaves, and the mail service commander requested her render, or to know the reason why she did non cull to render. The Mohaves initially sequestered Olive and resisted the request. At get-go they denied that Olive was fifty-fifty white. Over the course of negotiations some expressed their affection for Olive, others their fearfulness of reprisal from whites. The messenger Francisco, meanwhile, withdrew to the homes of other nearby Mohaves; shortly thereafter he made a second fervent endeavour to persuade the Mohaves to part with Olive. Merchandise items were included this time, including blankets and a white horse, and he passed on threats that the whites would destroy the Mohaves if they did not release Olive.

After some give-and-take, in which Olive was this time included, the Mohaves decided to accept these terms, and Olive was escorted to Fort Yuma in a 20-day journeying. Topeka (the daughter of Espianola/Espanesay and Aespaneo) went on the journeying with her. Before inbound the fort, Olive was given Western wearable lent past the married woman of an ground forces officeholder, as she was clad in a traditional Mohave skirt with no covering to a higher place her waist. Inside the fort, Olive was surrounded by cheering people.[6] : 111

Olive'southward childhood friend Susan Thompson, whom she befriended over again at this time, stated many years later that she believed Olive was "grieving" upon her return because she had been married to a Mohave man and had given nascence to two boys.[4] : 152 [22]

Olive, notwithstanding, denied rumors during her lifetime that she either had been married to a Mohave or had been sexually mistreated by the Yavapai or Mohave. In Stratton'south book, she declared that "to the honor of these savages let it be said, they never offered the least unchaste abuse to me." However, her nickname, Spantsa, may take meant "rotten womb" and implied that she was sexually active, although historians have argued that the name could have different meanings.[half dozen] : 73–74 [23]

Inside a few days of her arrival at the fort, Olive discovered that her brother Lorenzo was alive and had been looking for her and Mary Ann. Their meeting made headline news across the W.

Gallery [edit]

-

Olive Oatman, tintype, 1857[24]

-

-

Mohave woman with tattoos, 1883

-

Mojave Indians, 1855. Mollhausen, H. B., artist; Sinclair, Thomas Southward., lithographer;

After life [edit]

In 1857, a pastor named Royal Byron Stratton sought out Olive and Lorenzo Oatman. He co-wrote a volume almost the Oatman Massacre and the girls' captivity titled Life amidst the Indians: or, The Captivity of the Oatman Girls Among the Apache & Mohave Indians.[25] [26] [27] [28] It was a bestseller for that era, at 30,000 copies.[12] Stratton used the royalties from the book to pay for Olive and her blood brother Lorenzo to nourish the University of the Pacific (1857).[29] [xxx] Olive and Lorenzo accompanied Stratton across the state on a book tour, promoting the book and lecturing in book circuits.[29] Olive was a curiosity. Her boldly tattooed chin was on display and people came to hear her story and witness the blue tattoo for themselves. She was the kickoff known tattooed White American woman equally well as ane of the first female public speakers. Olive entered the lecture circuit as feminism was developing. Though she herself never claimed to be role of the movement, her story entered the American consciousness shortly afterward the Seneca Falls Convention.

Both Olive Oatman and Mary Brownish, Sallie Play a trick on's mother and Rose–Baley Party survivor, lived in San Jose, California, at the same time. Mary Brown refused a meeting.[31]

In Nov 1865, Olive Oatman married a cattleman named John B. Fairchild.[32] They met at a lecture she was giving alongside Stratton in Michigan. Fairchild had lost his brother to an assault by Native Americans during a cattle drive in Arizona in 1854, the time in which Oatman was living among the Mohave.

Stratton did non receive an invitation to the wedding, and Olive never reached out to him again. Though it was rumored that Olive died in a mental asylum in New York State in 1877, information technology was possibly Stratton who became institutionalized after the development of hereditary insanity and died shortly afterward.

Olive and John Fairchild moved to Sherman, Texas, a smash town ripe for a businessman like Fairchild to start a new and prosperous life. Fairchild founded the Urban center Bank of Sherman and together they lived quietly in a big Victorian mansion.[33]

Olive began wearing a veil to comprehend her famous tattoo [34] and became involved in clemency work. She was particularly interested in helping a local orphanage. She and Fairchild never had their own children, but they did adopt a little daughter and named her Mary Elizabeth later on their mothers, nicknaming her Mamie. Her hubby went on to track down copies of Stratton's book and burn down them.[33]

Grave Marker at West Hill Cemetery in Sherman, Texas

Death and legacy [edit]

Her brother Lorenzo died on October 8, 1901.[35] She outlived him by less than ii years.

Olive Oatman Fairchild died of a eye set on on March 20, 1903, at the age of 65.[36] She is buried at the West Hill Cemetery in Sherman, Texas.[37]

The boondocks of Oatman, Arizona, named for the Oatman family unit, founded equally a small mining camp when two prospectors struck a aureate find in 1915, was once a bustling mining and gambling boondocks that turned into a ghost town. Information technology was part of the Oatman Gold District.[38] The town is now a tourist terminate.[39]

The celebrated town of Olive City, Arizona, virtually the present boondocks of Ehrenberg, was a steamboat end on the Colorado River during the gilded blitz days, which was named in her honor. Other Oatman namesakes in Arizona are Oatman Mountain[twoscore] and Oatman Flat. Oatman Flat Station was a stage stop for the Butterfield Overland Mail from 1858 to 1861.

In popular culture [edit]

The graphic symbol of Eva Oakes, portrayed by Robin McLeavy, in the AMC television series Hell on Wheels is very loosely based on Olive Oatman. Outside of beingness captured by a group of Native Americans, bearing the distinctive blue chin tattoo, and having been raised Mormon, there are very few similarities between the character of Eva and the actual life of Olive Oatman.[41]

Novelist Elmore Leonard based a brusque story, "The Tonto Woman," on a white captive adult female who was tattooed in the manner of Oatman.[6] : 203

In an episode of the serial The Ghost Inside My Kid: The Wild W and Tribal Quest, a southern American Baptist family claims that their daughter Olivia says she is the reincarnation of Olive Oatman.[42]

In 1965, the actress Shary Marshall played Oatman, with Tim McIntire equally her blood brother, Lorenzo, and Ronald W. Reagan equally Lieutenant Colonel Shush, in "The Lawless Have Laws" episode of the syndicated western series Expiry Valley Days, hosted by Reagan well-nigh the end of his interim career. In the storyline, Burke leads Lorenzo in a search for his sister, whom he has not seen in five years since an Indian raid on their family.[43] [6] : 201

| Date | Title | Writer |

|---|---|---|

| 1872 | Who Would Take Thought Information technology? | Maria Amparo Ruiz de Burton |

| 1982 | The Tonto Woman | Elmore Leonard |

| 1997 | And then Broad the Sky | Elizabeth Grayson |

| 1998 | The Tonto Woman and Other Stories | Elmore Leonard |

| 2003 | Bribe'southward Marking | Wendy Lawton |

| 2009 | The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman [6] | Margot Mifflin |

Further reading [edit]

- Banks, Leo (1999). Stalwart Women: Frontier Stories of Indomitable Spirit. ISBN0-916179-77-X.

- "Olive Oatman – The Girl With The Blueish Tattoo". True West. March 2018. — details the road to and the location of "the start army camp of captivity"

- Baley, Charles West. (2002). Disaster at the Colorado : Beale's wagon road and the first emigrant party. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press. ISBN978-0-87421-437-6.

Free Download Full Text

- Oesterman, Melinda A. (2005). "Political factionalism amidst the Mojave Indians, 1826--1875". UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. doi:10.25669/rmpp-5mma. PDF

- Derounian-Stodola, Kathryn Zabelle (Oct 1998). "The Captive and Her Editor: The Ciphering of Olive Oatman and Purple B. Stratton". Prospects. 23: 171–192. doi:10.1017/S0361233300006311. "Buy article"

- A. L. Kroeber and Clifton B. Kroeber Olive Oatman's First Business relationship of Her Captivity Among the Mohave California Historical Society Quarterly Vol. 41, No. iv (December 1962), pp. 309-317 (ix pages) Published By: University of California Printing

- Bride, Sean H. ""A mark peculiar"- Tattoos in Captive Narratives, 1846-1857" (PDF). Academy of Winchester.

This Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree

- Mifflin, Margot (1 Baronial 2009). "ten Myths About Olive Oatman". True Westward Magazine.

- Mifflin, Margot (2001). Bodies of subversion : a hugger-mugger history of women and tattoo. New York: Juno Books. ISBN9781890451103.

- Schaefer, Jerry; Laylander, Don (2014). "A. K. Tassin's 1877 Manuscript Account of the Mohave Indians" (PDF). Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. 34 (1).

Encounter also [edit]

- List of kidnappings

- List of solved missing person cases

- Mary Jemison

- Frances Slocum

References [edit]

- ^ a b Powelson, Benjamin F. "Olive Oatman, circa 1863". 58 Country St, Rochester, NY.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ McLeary, Sherrie S. (June 12, 2010). "Fairchild, Olive Ann Oatman". tshaonline.org.

- ^ Braatz, Timothy (2003). Surviving Conquest. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Printing. pp. 253–54.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g McGinty, Brian (2005). The Oatman Massacre: A Tale of Desert Captivity and Survival. Norman: University of Oklahoma Printing. ISBN9780806137704. OCLC 1005485817. Retrieved July 31, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wild, Chris. "The story of the young pioneer girl with the tattooed confront". Mashable . Retrieved 2019-11-05 .

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mifflin, Margot (2009). The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Printing. ISBN9780803235175. OCLC 1128156875. The Blue Tattoo excerpt at the Wayback Car (archived 2016-03-06)

- ^ a b James, Edward T.; James, Janet Wilson; Boyer, Paul Southward. (1971). Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary . Harvard University Press. pp. 646–47. ISBN978-0-674-62734-v.

- ^ a b Rasmussen, Cecilia (sixteen July 2000). "Tale of Kindness Didn't Fit Notion of Savage Indian". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b Rowe, Jeremy (2011). Early Maricopa County: 1871–1920. Arcadia Publishing. p. 7. ISBN978-0-7385-7416-5.

- ^ a b "The Murder at Oatman Flat". The Tucson Citizen. Tucson, Arizona. September 27, 1913. p. iv. Retrieved August i, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Baker (1981). "Mapping the Southwest". The American Due west. Vol. xviii. pp. 48–53.

- ^ a b Stratton, Royal Byron (1858). Captivity of the Oatman Girls: Being an Interesting Narrative of Life Among the Apache and Mohave Indians (Third ed.). New York, New York: the author, by Carlton & Porter. Retrieved iii February 2022 – via annal.org.

Original from the Academy of California Digitized: 2006-x-10

- ^ "History of Mojave Indians to 1860". August 18, 2000. Archived from the original on August 18, 2000.

- ^ "Olive Oatman". mojavedesert.net.

- ^ Kroeber, Alfred L. (1962). "Olive Oatman's First Account of Her Captivity Among The Mohave". California Historical Society Quarterly. 41 (four): 309–317. JSTOR 43773362.

- ^ "Mojave Tribe: Culture". Mojave National Preserve. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ "Mohave. Adult female with chin tattoos, ca. 1900". vanishingtattoo.com.

- ^ "Marks of Transformation: Tribal Tattooing in California & the American Southwest by Lars Krutak". vanishingtattoo.com.

- ^ "Images of Native Americans : Mass Market Appeal (xi of 19): Royal B. Stratton: LIFE Amongst THE INDIANS". The Bancroft Library . Retrieved 2021-03-23 .

- ^ Blattman, Elissa (2013). "The Abduction of Olive Oatman". National Women's History Museum.

- ^ "The Blueish Tattoo | The Mohave Indians | Olive Oatman". ralphmag.org.

- ^ Dillon, Richard H. (1981). "Tragedy at Oatman Flat: Massacre, Captivity, Mystery". American West. Vol. 18, no. ii. pp. 46–59.

- ^ Lawrence, Deborah; Lawrence, Jon (2012). Violent Encounters: Interviews on Western Massacres. Academy of Oklahoma Printing. pp. 27–28. ISBN978-0-8061-8434-0.

- ^ "Tintype portraits of Olive Oatman and Lorenzo D. Oatman". via: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University

- ^ Stratton, Royal Byron (1858). Captivity of the Oatman Girls: Being an Interesting Narrative of Life Among the Apache and Mohave Indians (Tertiary ed.). New York, New York: author. Retrieved 3 February 2022 – via google books.

Original from the New York Public Library Digitized: 2007-12-18

- ^ Stratton, Purple Byron (1858). Life among the Indians: or, The Captivity of the Oatman Girls Amongst the Apache & Mohave Indians (Tertiary ed.). New York, New York: Author. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

Original from the Academy of Michigan; Digitized: 2005-xi-23

- ^ Stratton, Royal Byron (1859). Captivity of the Oatman Girls: Being an Interesting Narrative of Life Amid the Apache and Mohave Indians. New York, New York: Author. Retrieved 3 Feb 2022 – via google books.

Harvard University drove Digitized from Original

- ^ Stratton, Royal Byron (1935). Life among the Indians: or, The Captivity of the Oatman Girls Among the Apache & Mohave Indians. San Francisco: Grabhorn Printing. Retrieved iii Feb 2022 – via Online Books Page.

- ^ a b "Fairchild, Olive Ann Oatman". Texas Land Historical Association. 2010-06-12. Retrieved August x, 2012.

- ^ "Calisphere: Olive Oatman, ca. 1860". Calisphere.

- ^ Baley, Charles Due west. (2002). Disaster at the Colorado : Beale's wagon route and the kickoff emigrant party. Logan, UT: Utah State University Printing. p. 125. ISBN978-0-87421-437-half dozen.

Free Download Full Text

- ^ "Story of Olive Ann Oatman is told". Herald Democrat.

- ^ a b "Flashback: Olive Oatman was D-FW'southward own Girl with the Chin Tattoo". Dallas News. 2017-08-22. Retrieved 2021-03-23 .

- ^ Vaughan, R.C. (January 11, 2009). "Veiled Lady Causes Stir on Sherman Streets". Sherman Democrat.

- ^ "Lorenzo Oatman". Geni. August 17, 2015.

- ^ Mae, Poppy (7 December 2017). "Olive Oatman & the Mohave Tribe". Medium.com . Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ Ashby, Linda (2011). Sherman. Arcadia Publishing. p. 17. ISBN978-0-7385-7983-2.

- ^ Ransome, F. L. (August i, 1923). "Geology of the Oatman gold district, Arizona". doi:ten.3133/b743 – via pubs.er.usgs.gov.

- ^ Varney, Philip (1994). Arizona Ghost Towns and Mining Camps. Arizona Department of Transportation, Land of Arizona. p. 1905. ISBN978-0-916179-44-1.

- ^ "Oatman Mountain : Climbing, Hiking & Mountaineering". SummitPost.

- ^ Hsieh, Veronica (November 2011). "Hell on Wheels Handbook – Olive Oatman, a Historical Counterpart to Eva". AMC Network Amusement LLC . Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ "The Wild West and Tribal Quest". The Ghost Inside My Child. Flavor 1. Episode three. thirty Baronial 2014. Lifetime.

- ^ "The Lawless Have Laws on Death Valley Days". Internet Movie Information Base. October 1965. Retrieved Baronial 27, 2015.

External links [edit]

- van Huygen, Meg (16 November 2015). "Olive Oatman, the Pioneer Girl Who Became a Marked Woman". Mental Floss.

- "Olive Oatman". Tattoo Archive.

- "Lot 12312: Mohave Indian". Library of Congress.

hendersoncousemen.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olive_Oatman

0 Response to "Mrs Ann White and Baby Daughter Abducted by Apache?"

Post a Comment